Billions of dollars are pouring into artificial intelligence as companies jockey for dominance. It’s hard not to see shades of the late 1990s internet bubble in today’s AI frenzy. But while history may not repeat, it offers valuable lessons for possible risks and opportunities.

Artificial intelligence: It’s real, and it’s spectacular

Artificial intelligence (AI) has been around for over a decade, but only recently has it become mainstream—capturing headlines and attracting massive investment from governments, institutions, and individuals. Like the internet before it, AI will reshape economies and societies. The race to capture this enormous market has sparked staggering capital investment, with major players leapfrogging each other in AI development. This raises two key questions: Will these investments pay off? And will AI be dominated by a single winner, or will it support multiple players? History may not repeat exactly, but past breakthroughs offer valuable clues for what’s ahead.

Capital expenditure: A tale of two booms

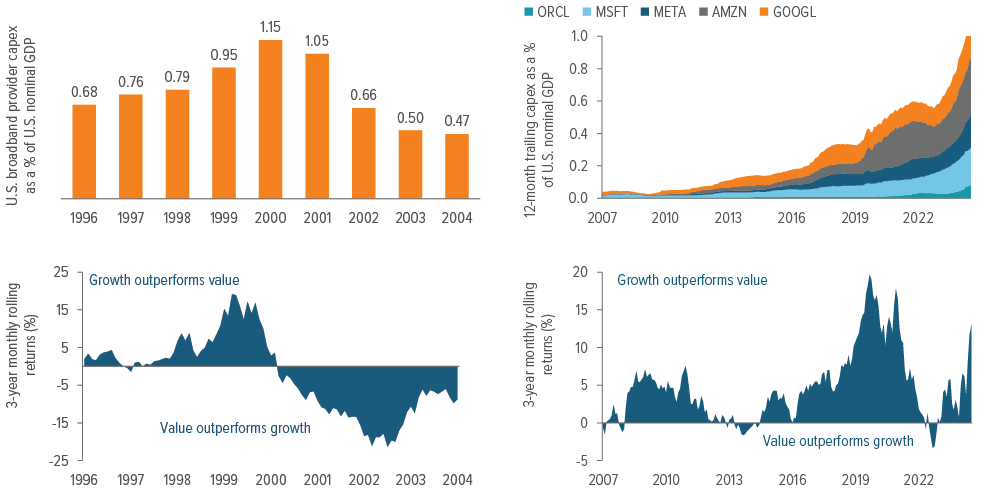

One of the clearest parallels to today’s AI boom is the internet buildout in the 1990s. Similar to today, it required massive upfront capital investment. During the internet era, U.S. broadband providers nearly doubled their capital expenditures (capex) as a percentage of GDP in just five years (1996-2000).

Capex growth proved unsustainable, and spending fell sharply, from 1.05% of GDP in 2001 to 0.66% one year later, triggering the dot-com bubble burst. Many companies were left with excess capacity and assets that didn’t generate expected returns. Growth investors enjoyed dramatic gains during the capex investment surge, but as spending slowed, growth stocks suffered steep drawdowns while value stocks rebounded (lower-right chart).

Today, we see a similar pattern in the AI sector. Over the last two years, the 12-month trailing capex as a percentage of GDP has doubled as the hyperscalers race to build the infrastructure for the next wave of technological transformation.

Source: FactSet, Voya IM. Top chart, left: Data represent capex as a % of U.S. nominal GDP from 1996 through 2004 for U.S. broadband providers. Top chart, right: Data represent the 12-month trialing capex as a % of U.S. nominal GDP from 12/07-07/25. Bottom charts: Data represent the returns of the Russell 1000 Index on a 3-year monthly rolling basis from 01/85 through 07/25.

Tech adoption vs. stock mania creates a timing mismatch

Alongside the surge in capex, market enthusiasm has far outpaced actual technology adoption. Historically, stock valuations often price in future growth before it materializes. This sets the stage for “indigestion” periods, when markets adjust to slower adoption or disappointing results. The internet bubble is a classic example: Prices soared on expectations for a digital revolution, but companies failed to deliver, triggering sharp corrections. The Nasdaq peaked in March of 2000 and didn’t reclaim that level for 15 years.

Consider the plight of Netscape. It captured early investor excitement given its first-mover’s “right to win,” but Microsoft leveraged its scale and distribution by bundling Internet Explorer with Windows, crushing Netscape’s advantage. Netscape’s growth narrative collapsed, and it was sold to AOL in 1998 for a fraction of its peak market value.

OpenAI, parent of ChatGPT, may be experiencing a “Netscape moment.” Like Netscape, OpenAI is a first mover but its $1.4 trillion compute obligations seem economically unrealistic, far beyond what organic cash flow could likely support—leaving it reliant on external financing. Meanwhile, Google (like Microsoft 25 years ago) is flexing its incumbency advantages with Gemini 3. This exposes a fault line in the AI arms race, likely risking those reliant on OpenAI achieving its capex ambition. If expectations unravel and the market proves “winner takes all,” we could see a sharp capex pullback and a broad revaluation of AI and growth stocks—echoing the dot-com implosion.

Lessons for investors

The AI boom mirrors the internet bubble as companies pour billions into data centers and hardware, betting future demand will justify the investment. As with the internet, the enthusiasm for AI has fueled a substantial capital cycle, benefitting a broad array of infrastructure providers. However, as investors begin to call into question the sustainability of this capex, the risk of indigestion looms large. For investors, the challenge is separating sustainable growth from speculative excess. As the cycle matures and spending rationalization takes hold, we fully expect a change in market leadership.

A note about risk: The principal risks are generally those attributable to investing in stocks and related derivative instruments. Holdings are subject to market, issuer and other risks, and their values may fluctuate. Market risk is the risk that securities or other instruments may decline in value due to factors affecting the securities markets or particular industries. Issuer risk is the risk that the value of a security or instrument may decline for reasons specific to the issuer, such as changes in its financial condition. Artificial intelligence (AI) including natural language processing, machine learning, and other forms of AI may pose inherent risks, including but not limited to: issues with data privacy, intellectual property, consumer protection, and anti-discrimination laws; ethics and transparency concerns; information security issues; the potential for unfair bias and discrimination; quality and accuracy of inputs and outputs; technical failures and potential misuse. Reliance on information produced using AI-based technology and tools should factor in these risks.