If 2025 was a year of disruption, the next looks more like a year of reckoning.

Financial markets are entering the new year with a mix of confidence and unease. Consumers remain resilient, capital spending is on the rise, and earnings expectations still look healthy. At the same time, investors are navigating the impending change in Fed leadership, watching pockets of stress in credit markets, and digesting the implications of events in Venezuela. Against that backdrop, the questions facing investors are becoming sharper. Are the rate cuts nearing their natural floor? How durable is the economic expansion? Where are credit risks still being mispriced? And how should investors think about artificial intelligence—not just as a growth engine, but as a force reshaping labor markets, capital allocation, and global competition? In this roundtable, our investment leaders tackle those questions and more. They debate the durability of the AI trade, the implications of a more nuanced credit landscape, and the uneven impact of automation on jobs and productivity. This is not a forecast built on a single narrative. It’s a conversation shaped by competing signals, real tradeoffs, and the recognition that 2026 is unlikely to be a smooth year, even if it proves to be a constructive one. Eric Stein, CFA |

The Venezuela surprise

Editor’s note: The initial roundtable discussion for this article took place in mid-December. In the wake of U.S. military action in Venezuela on January 3, we reconvened to discuss the market implications.

Does Venezuela change the geopolitical and energy calculus for 2026?

Eric Stein: Let’s talk about what happened over the weekend. It’s clearly a fluid situation, but the Trump administration’s move in Venezuela reflects a much more assertive, regionally focused strategy— almost a modern Monroe Doctrine. That has implications not just for Latin America but for how Russia and China think about their own regional positions.

Barbara Reinhard: I’d put some guardrails around it. The U.S. is clearly emphasizing resource security in the Western Hemisphere. But in terms of near-term global impact, Venezuela is small. It’s about 0.1% of global GDP and roughly 1% of oil supply. Production capacity has collapsed, and any recovery would take years. That’s why markets have stayed relatively calm. Energy stocks are reacting, but we haven’t seen much movement in rates, the dollar, or oil prices yet. The rally in Venezuelan bonds reflects niche restructuring optimism, not a broad signal.

Jim Lydotes: It’s potentially meaningful for the energy sector. Even though current production is minimal, Venezuela has the largest proven oil reserves in the world. If U.S. companies are able to invest there, you’re talking about a very different growth backdrop for energy equities. U.S. energy stocks have spent years being treated as defensive, cash-return vehicles. If there’s a credible path to rebuilding Venezuelan energy infrastructure, that flips the narrative back toward growth. It would be a big change for how investors think about the sector.

An opportunity to rebuild Venezuelan energy could flip the narrative for the U.S. energy sector.

Stein: So a limited impact in 2026, but it adds optionality in the long term.

Reinhard: And from an inflation standpoint, even the prospect of more supply helps cap risks over time, which policymakers and markets will be watching closely.

Macro crosscurrents

Are rate cuts nearing an end?

Stein: Let’s rewind the tape to the December Fed meeting. Chairman Powell sounded very much like an asset manager, framing things around the distribution of possible outcomes.

Jeff Hobbs: Right, he certainly didn’t sound like a lame duck, even with a new chair expected to be announced soon. The range of opinions among Fed voters seemed fairly balanced, with some wanting to cut more but plenty of others preferring to stay on pause. Given how closely Fed decisions have become tied to the White House, a June rate cut feels very much in play. But there’s not much room for aggressive easing either. So let’s say one cut in March and one in June, and then that puts you close to the bottom of this rate cycle.

Reinhard: The most important signal to our team was around the labor market. Powell indicated that payroll growth is likely being overstated by about 60,000 jobs per month. We’ll have to see how that plays out, as we don’t see that type of weakness in the unemployment claims or the JOLTS data. But if the Fed is concerned about the labor market, it would be more likely to cut rates in 2026.

Stein: Does the upcoming Fed chair appointment actually matter, or is it just noise?

Reinhard: We think it matters to the markets. The Fed chair is the spokesperson for the 12-member FOMC, which sets monetary policy. It’s important not to lose sight that monetary policy is set at the committee level, but the chair is an important part of its leadership. Every new Fed chair going back to the 1950s has been tested by markets early in their tenure. Investors will be looking for clues on the direction of rates, so every comment by the new chair will be scrutinized and subjected to interpretation. That means asset price volatility of some degree is almost inevitable, no matter who’s nominated.

Every new Fed chair gets tested by markets early in their tenure. Volatility is almost inevitable.

Hobbs: I think back to “Liberation Day” in April, and what ultimately got Trump to reverse course on tariffs was the reaction in the Treasury market. There’s clearly a push for a more dovish Fed, but there’s also a sensitivity to how markets respond to different candidates, since the goal is getting the 10-year yield lower to support growth.

Stein: If the back end of the curve sells off too much, especially with the mounting fiscal pressure, it becomes self-correcting in terms of who Trump ends up picking to helm the Fed.

Will 2026 be a breakout year for the economy?

Stein: Let’s broaden this out beyond the Fed. Jim, how do you see the backdrop shaping up from an equity perspective?

Lydotes: It’s looking pretty good. Consumer data has been really strong over the last couple months, outside of housing. And some of the new federal tax benefits will start kicking in. The other key is that capital expenditure intentions are being revised higher. That’s one of the strongest indicators of management confidence. And it’s not just about building data centers. It’s happening in both large caps and small caps and across sectors. That’s a healthy sign.

Reinhard: I agree, and I’d frame it around three factors. First, U.S. earnings growth is projected at 13.5% in 2026, 1 which is a strong signal for stocks. Second, NFIB hiring intentions showed some sign of improvement late in 2025, and that typically leads employment by about six months. Lastly, fiscal policy will flip from being a drag in 2025 to a positive force in 2026. Tax relief around tips and parts of Social Security should help middle-income consumers who’ve been under pressure from tariffs.

13.5% projected earnings growth is a strong signal for U.S. stocks.

Hobbs: We’ve described this as a “jobless rolling recovery.” Growth was muted in the first half of 2025, but we expect it to pick back up in 2026. Easier financial conditions, a rebound in rate-sensitive sectors like housing, and the broader tailwinds the others have mentioned all support that view, which is consistent with tight credit spreads.

Credit fault lines

Are isolated credit events masking deeper risks?

Stein: We’ve talked about some constructive themes, but there are also some areas where risk may not be fully priced in. Mohamed, from your vantage point with bank loans and the First Brands bankruptcy in particular, what’s the environment for leveraged credit?

Mohamed Basma: First Brands has obviously been a hot topic for us. We see it as an isolated issue, with alleged fraud being the primary driver. There may have been some red flags along the way, but we don’t see it as a systemic credit issue or representative of general underwriting standards in the broadly syndicated loan (BSL) market.

Still, some idiosyncratic risks were front and center in 2025, and it won’t surprise me if we encounter other similar situations going forward. We’re watching sector-specific weakness in chemicals, packaging, cyclicals, and building products. And AI-related risks have now entered the conversation as well.

But when you zoom out, the fundamentals for BSLs are largely stable. Earnings aren’t as strong as they were in 2024, but stress indicators—loans trading below 80 and triple-C exposure—are contained. And at the other end of the tail, the share of loans trading above par is at a historical high.

What’s less discussed is the growth of loans trading in the 80-95 range. That’s where we’ve seen the landmines and continued bifurcation trends.

We believe First Brands isn’t representative of general underwriting standards in the BSL market.

Where are the real vulnerabilities in leveraged credit in 2026?

Stein: One of the challenges facing both leveraged credit and high yield private credit is declining documentation and covenant quality. What’s driving that?

Basma: There are two things: High yield private credit funds are sitting on a half a trillion dollars of dry powder and are under enormous pressure to deploy it.2 Second, banks have come roaring back into the corporate loan market after the Trump administration rolled back regulations in early 2025. That’s creating intense competition for high yield direct lenders on both pricing and structure, and it’s contributing to further loosening in credit documents for syndicated bank loans.

Stein: Which is then indirectly tied to the rise of liability management exercises (LMEs).

Basma: Right, so we’re now seeing both sponsors and public issuers engage in coercive LME transactions. Not just the typical distressed exchanges, but aggressive structures that shift value away from syndicated loan lenders towards sponsors and equity holders.

That’s been a defining theme for us. Looking ahead, return expectations for the asset class are around 5-6%, likely below the coupon, which is closer to the mid-6s. That reflects spread compression, lower base rates, and declining recoveries. Historically, recoveries were closer to 70; today, with LMEs, they’re closer to 50.

Technicals are likely to soften in 2026 as M&A activity picks up and supply increases. That could actually help ease some of the pressure on spreads due to the severe demand/supply imbalance of the past few years. Collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) will remain a major source of demand (about 75% of the market). But equity arbitrage has become less attractive, which likely means lower CLO issuance than we’ve seen recently.

All in all, the backdrop is still constructive. But we’re watching consumer health and fourth-quarter earnings, which will give a clearer picture of the second-order impacts of tariffs.

Private credit markets are less stressed than in 2022-23, and spreads on origination remain attractive.

Where is risk being mispriced in private credit?

Stein: Jeff, taking a broader view of private credit, where do you see opportunities and where are the stress points?

Hobbs: Starting with private credit, our focus has traditionally been investment grade— private placements and project finance— where the opportunity set is still solid. In 2025, our average origination spread was about 215 basis points over Treasuries,3 very much in line with what we’ve done over the past two decades for similar BBB+ risk.

That’s especially attractive given where public spreads are right now.

The main area of concern is where debt growth has been most aggressive, especially in high yield private credit, which has grown from essentially zero in the 2000s to about $2 trillion.4 Much of that growth occurred during the zero-rate era, and that’s where you see the lighter covenants that Mohamed mentioned and limited subordination. Still, default rates around 4.5–5.5% aren’t out of the ordinary, and in fact stress has eased relative to 2022-23 as front-end rates have normalized.

Do securitized markets still offer relative value?

Stein: Within public markets, spreads for securitized credit have tightened from where they were a year ago. But you’ve said there are still opportunities there next to super-tight corporate spreads.

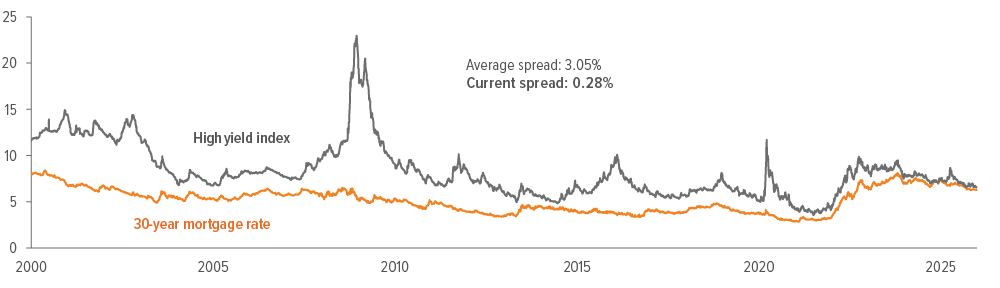

Hobbs: I’d say anything that rhymes with “mortgage” looks interesting. Thirty-year mortgage rates are near 25 basis points of the yield to worst on high yield bonds, which is unusual. Residential mortgages still screen as cheap, and in commercial real estate, prices remain roughly 10% below 2022 peaks,5 with lending spreads that look attractive. There are some interesting spots in asset-backed securities and asset-based finance to help diversify collateral. So it’s an interesting space even as spreads have tightened.

What’s driving the convergence of public and private debt markets?

Stein: Let’s dig into this trend where the line between public and private credit is becoming more blurred. Mohamed, you grew up in the loan asset class, which has been positioned somewhere between high yield and direct lending. How do you see things evolving across the leveraged credit space these days?

Basma: The market has come to terms with the need for both sides to coexist. When sponsors think about accessing capital markets for financing mid-to-large below investment grade issuers, they now have a playbook with three primary options: secured bonds, broadly syndicated loans, and private credit. Which one they choose depends on prevailing market technicals and ease of syndication execution.

In 2022 and 2023, the BSL market lost a lot of deals to private credit due to unfavorable conditions. Private credit facilitated some of the trickier transactions (think highly levered software deals) that the loan market just couldn’t finance. But in the last few months, the syndicated loan market is winning back some of those deals, since sponsors can often lower their spreads by 200-300 basis points accessing the BSL market.

Stein: Jeff, what does convergence look like on the investment grade side?

Hobbs: Traditionally, IG private fixed income served smaller companies or projects that didn’t need frequent access to public markets, so they would work with a club of lenders, mostly insurers. What’s changed is how large public investment grade companies are using private markets as a form of off-balance-sheet financing.

For example, in the third quarter, Meta had a data center transaction that started in the private market, then migrated into the public market as the single-largest off-index 144A CUSIP. That grabbed attention across both markets. It structured the deal to keep operating leverage off balance sheet while also accessing unsecured public debt elsewhere in the capital structure.

Private markets still offer more flexibility around terms and tenors, and there’s a structural premium for lenders. But the nature and scale of transactions have clearly evolved, and the line between public and private financing is far less distinct than it used to be.

Large companies are using private markets to keep operating leverage off balance sheet while also tapping the unsecured corporate bond market.

AI’s next phase

What’s really driving AI investment today?

Stein: Let’s switch gears to a theme that dominated 2025. Investors are probably wondering how to make sense of all the AI headlines. Sebastian, you lead our global AI strategy. What stands out to you?

Sebastian Thomas: I think it’s the sustained demand for compute and how that’s driving capex higher as companies build out inference. The focus used to be on training large models. Now, it’s about infusing AI into existing systems. Workloads that were previously handled by human-designed algorithms are being upgraded to AI-driven ones that are far more capable and responsive.

This is a massive undertaking, and companies are short compute capacity to stand up the applications they want. Because of that shortage, they continue to increase capex. The challenge is that supply chains weren’t designed for this kind of step-function increase—whether it’s storage, memory, or optical networking.

So suppliers are asking hard questions: Do we expand capacity aggressively? How long does this AI buildout last? If it’s only a few years, does it make sense to overbuild? That uncertainty is introducing some rationality, but it’s also contributing to persistent shortages.

The driving force today is about infusing AI into existing systems, which is a massive undertaking.

Where are the competitive fault lines emerging in AI?

Stein: Jim Dorment, you’ve referred to the AI arms race in terms of Axis and Allies. Not in the sense of taking sides, but in how it’s creating distinct ecosystems that investors need to understand.

Jim Dorment: Until recently, there was a rising-tide element to the AI trade. Almost everything benefited. But the success of Google’s Gemini 3 model highlighted a fault line emerging in the marketplace. We think about two broad ecosystems. One is disproportionately tethered to OpenAI. The other is centered around Google, with Apple historically intertwined there, and Broadcom as the leader in custom ASICs. That distinction matters because it brings economics into focus.

Not that long ago, the market seemed to think there was very little probability that OpenAI might struggle to meet its long-term obligations. But when you start talking about numbers like $1.4 trillion of capex over 10 years, you have to ask whether any single player has a right to win by default.

We use the Netscape analogy. It’s not perfect, but it illustrates how incumbency can matter when products become “good enough” and scale advantages kick in. OpenAI is taking on multiple incumbents at once—hardware, messaging, platforms— which means a lot of bets will have to win in order to underwrite $1.4 trillion of spending. Then downstream from that, you have Nvidia, Oracle, and others tied together through what you could almost call circular financing.

So as we go from a rising-tide environment to competing ecosystems, we expect some dynamic trading opportunities around the Google complex and the OpenAI complex. And then as a consequence of this, given the systemically important nature of AI infrastructure, I wouldn’t rule out some form of government involvement down the line to help OpenAI underwrite its obligations— and that’s your Marshall Plan.

Just as we saw with Netscape, no single player has a right to win by default.

Where are the most investable areas in the AI ecosystem today?

Stein: The key thing with AI is implementation. It’s clearly taking off, but there’s still a big divide in how companies are approaching it.

Lydotes: Investor relations teams are clearly pushing management to talk about it. About two-thirds of S&P 500 companies mentioned AI on their third-quarter earnings calls. It makes me wonder what’s going on with the other third. But then again, a Census Bureau survey showed only roughly 20% of U.S. businesses reported either using AI or planning to use it in the next six months.6 It means that companies outside of tech and communication services are just starting to embrace AI in a practical way. The ones that can actually use it to enhance productivity, improve margins, or change how they operate will separate themselves. That’s going to be a major driver of differentiation in 2026.

Stein: Sebastian, let’s go more granular. Where do you see the best opportunities within the AI value chain?

Thomas: A lot of it comes down to constraints. Companies are dealing with severe bottlenecks throughout the supply chain. Optical networking is a good example—firms are trying to link data centers to synchronize training runs across clusters, and that’s driving strong demand. High-bandwidth memory is another area where pricing has moved meaningfully. So when you see big headlines like Oracle’s massive cloud backlogs, that can be a double-edged sword, because companies still have to procure scarce components, often competing against others that have been building data centers for years. And internationally, suppliers into this buildout are becoming increasingly important.

Networking will be a key theme as companies try to connect more GPUs and clusters to deliver more intelligence.

How is AI capex being financed?

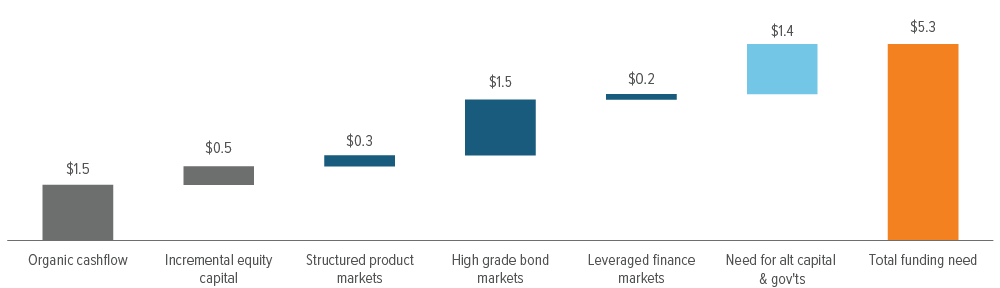

Stein: All this AI capex has to be funded. Where is the money coming from?

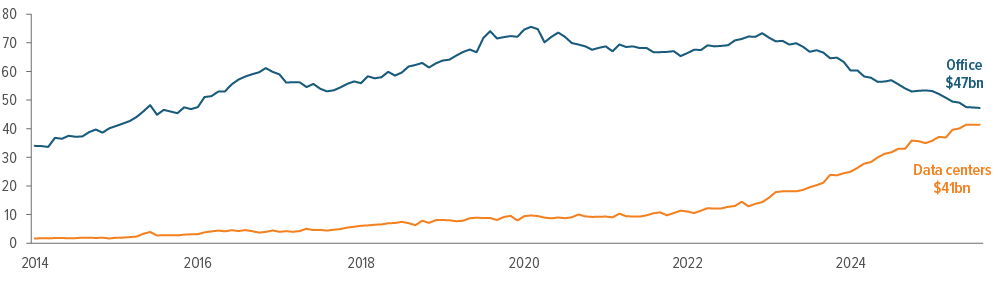

Hobbs: The short answer is that it’s coming from everywhere. Before the 2008 financial crisis, the tech sector made up less than 3% of the U.S. investment grade corporate bond index. Today it’s closer to 10% and rising quickly.7 That means a lot of AI capex is showing up on balance sheets through public debt, but it’s increasingly moving off balance sheet through lease obligations, particularly among hyperscalers. The economic exposure to AI is still there, even if it doesn’t always look like traditional debt.

Stein: And Mohamed, you lend to highly leveraged businesses that worry about disruption. How does AI factor into your underwriting today?

Basma: That question has moved right to the top of the list, alongside discussions around respective business models, revenue drivers, input costs, margin pressure, and cash flows. It’s one of the first things we now ask in our investment committee meetings: How could this business be disrupted or disintermediated by AI? Could it become obsolete? You see this most clearly in software, which makes up a meaningful portion of the loan market. The business models are technical, opaque, and potentially vulnerable to rapid disruption. So for lenders, AI isn’t just about growth—it’s about durability.

As of 11/30/25. Source: JP Morgan.

Labor in transition

Where is AI already disrupting the labor market?

Stein: The other thing we have to address is the impact AI is having on jobs. I’m curious to see how society ultimately responds to it.

Thomas: We’re already seeing a clear tradeoff inside the tech sector. Companies are increasing capex to fund AI infrastructure while they’re also pruning labor to make room for that spend. More broadly, companies are shifting capital to areas where they see significantly higher returns, which in many cases is AI. There are more anecdotes about companies rolling out “AI teammates” that can automate certain tasks, such as building a marketing brief, researching a market opportunity, drafting a report, or preparing a presentation. That kind of technology really hurts opportunities for entry-level work.

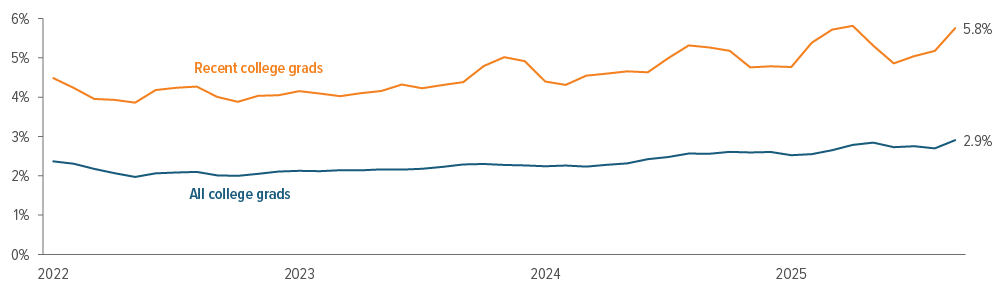

You see it in the difference in unemployment between recent grads and all college graduates over the past few years. AI is likely playing a role there, because those early-career jobs are often the most exposed to displacement.

As of 12/17/25. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Workers with bachelor’s degree or higher, ages 22-27 vs. ages 22-65.

Stein: AI is also creating massive numbers of blue-collar jobs to build data centers, power infrastructure, and everything in that ecosystem. Jeff, how does this play out from a macro perspective?

Hobbs: Over the past few months, unemployment for workers without a high school degree or college education has actually fallen, even as broader unemployment has ticked up. So you’re seeing a divergence between lower-skill blue-collar jobs earning six-figure salaries and lower-skill white-collar jobs that are being eliminated.

Stein: It reminds me of Western Australia’s commodities boom in 2010, where people were making extraordinary money during the buildout, only to see it collapse when demand from China rolled over. This feels similar.

Hobbs: It’s clearly good for blue-collar employment right now, but capex-driven demand is cyclical by nature. The build phase creates intense demand, but it doesn’t necessarily translate into long-term employment at the same scale. When the cycle turns, the adjustment can be painful. You’re likely left with higher structural unemployment as the economy transforms and skills don’t line up cleanly with demand.

The data center boom is great for blue-collar workers today, but it could be a painful adjustment when the capex cycle turns.

As of 12/31/25. Source: U.S. Census Bureau.

Dorment: One thing I’ve been thinking about is how this could distort productivity numbers. If you’re moving workers into blue-collar construction roles, which are inherently less productive on a per-worker basis, you could actually see reported productivity numbers get suppressed in the short term. AI is supposed to be a productivity story, but the transition creates noise and even the potential for disappointment. If labor temporarily shifts into lower-productivity jobs while AI benefits accrue elsewhere, the data may not immediately show the gains everyone expects.

Investable ideas for 2026

Stein: Let’s close this out with a quick turn around the room. What is your favorite trade for the coming year, and then one big surprise?

Lydotes: For me, it’s healthcare. The sector is starting the year in a very good place after being dramatically out of favor. It typically performs well heading into a midterm election year, and many of the regulatory headwinds that weighed on it have now eased. There’s simply much better visibility than there was a year ago.

For a surprise call, I’ll say downside risk to the power narrative fueling AI. I’m generally very bullish on AI, but there’s risk in public equities on the power side of the trade. There’s a chance we find more efficiency in power usage even as AI use cases accelerate. If that happens, some of the more power-exposed parts of the AI supply chain could turn out to be overbuilt.

Hobbs: My top pick at the moment is mortgage-related assets. Agency-backed residential mortgages are already yielding broadly the same as much riskier high yield bonds, and then careful leveraging of those bets with mortgage derivatives—which can be a surprisingly low-volatility strategy thanks to our team’s ability to research the underlying mortgage pools—has real potential for outperformance.

A surprise could be where you see this “creditor-on-creditor violence” that has plagued the leveraged market seep into the investment grade space. With the pickup in M&A, companies could structure things to keep long-duration, low-dollar bonds outstanding while they re-lever their cap structures. The Warner Bros. Discovery transaction was an example of bondholders being negatively impacted by M&A, and markets aren’t pricing in more of that type of behavior.

Basma: Mine will sound boring given the markets we operate in. Loans have generally been an all-weather asset class. We’d be very comfortable generating a 5-6% return from coupon-clipping, less some detraction for credit losses, spread compression, and market value changes. I think 2026 could be a slightly lower-coupon year, but one with a lot of opportunity for credit selection and differentiation.

The surprises in credit markets are going to come from these idiosyncratic landmines to navigate. That’s a situation where I think our style works well, building a high-quality portfolio and using dislocations to act selectively.

Dorment: Jim stole my pick for healthcare, so I’ll talk about regional banks. They underperformed money-center banks meaningfully in 2025, and there are some attractive names that are well positioned for deposit and fixed-asset repricing. Loan growth is accelerating, and there’s credible M&A optionality as deregulation encourages further consolidation.

For surprises, I’ll give you two. First, disillusionment with AI data center capex eventually shifts the focus to companies that would benefit from AI inference “at the edge,” where requests are processed locally. And second, the biggest dominoes have yet to fall with regard to consolidation of Big Media.

Thomas: Jim, let me build on what you said about the Mag 7. My surprise pick is the rest of the S&P 500 outperforms the Mag 7 in 2026. These companies are engaging much more with debt markets than they historically have, and more capital is being committed to infrastructure than to share buybacks and returning cash to shareholders. That alone could weigh on relative performance.

But for my best idea within tech, networking is the real theme. As more GPUs and larger clusters are connected to deliver more intelligence, things like test-time compute (the extra time and processing power AI models use to refine answers) and more advanced reasoning models will require far more networking. That includes optical networking, which I believe will see a durable revival.

Stein: Barbara, your call last year on gold worked out pretty well. What are you seeing for 2026?

Reinhard: We’ve long-favored U.S. stocks over the rest of the world, but the emerging markets are looking more attractive to us. The move lower in the U.S. dollar has helped, and China is likely to stimulate its economy later this year. We also think Japan looks very interesting. Corporate reforms are continuing, buybacks are in full swing, and the new political leadership is likely to deliver a further fiscal push.

For a longshot, watch Europe. It was unloved by global investors for most of 2025 due to its sideways consolidation since last March. More fiscal easing by Germany, an improving credit impulse, and a rebound in earnings could all be catalysts for a meaningful rally.

Stein: Those are some interesting calls. For me, small caps stand out given where we are in the economic cycle. Interest rates seem fairly contained, and if the Fed gets a more dovish leadership tilt, that’s good for small cap stocks.

And my pick for a surprise is the unexpected scale of improvement in large language models. With so much money at stake and the reward for getting it right, today’s concerns around model hallucinations will be the hallucination itself. The disruption to industries and societal implications will be massive. 2026 is going to offer a front-row seat to history.

Thank you all for a thoughtful discussion. To our clients, we look forward to continuing these conversations with you as markets continue to evolve in 2026.