As we head into the final stretch of hotly contested races up and down the ballot, our experts convene for civilized discourse on what matters to markets and what doesn’t.

| In just a few weeks, the American people will decide the policies and personalities that will steer the fate of the United States for the next four years—not just who inhabits the Oval Office, but whether a single party can gain control of both the House and the Senate. The next president will guide an economy more than 100 times the size of FDR’s America, and the trend of expanding executive power means that either Harris or Trump can accomplish quite a bit even if faced with an oppositional Congress, setting the agenda for regulatory agencies, energy policy, artificial intelligence, trade and foreign aid. Big elections tend to swing on the economy. However, the start of the Fed’s cutting cycle plus broad economic stability suggest it will only be one of several issues dominating the political debate. While all the policies at stake in the 2024 election are important, only certain ones are likely to move markets over the longer term. Our panelists discuss how key policy differences might play out under various post-election scenarios, and how these could affect investment portfolios. Be prepared for heightened market volatility in the run-up to November 5th. Until then, as Barbara says below, don’t lose sight of the ball. |

Panelists:

Economic context: Slowing not stalling

Eric Stein: Voters consistently say the economy is their number one issue, and it’s often a good predictor of election outcomes. Are any of you concerned about where the economy is going?

Barbara Reinhard: The weak jobs numbers shook everybody a bit because the labor market had been so strong for so long. But inflation has been coming down significantly from its peak two years ago, wage growth is manageable, and the economy is still chugging along at a slightly above-trend pace. Rate cuts will take a while to flow through to support the economy, just as rate hikes took a while to bite the economy on the way up. In the meantime, the rest of the world isn’t doing especially well from a growth standpoint. China’s economic releases for August have been quite weak, and Europe is dealing with political and structural challenges. Similar to the late 1990s, the U.S. is the highlight of the global economy.

Recession risk

The economy isn’t exhibiting the buildup of excess that often precedes a significant recession.

Sean Banai: Risks to the economy have increased, but the chance of a recession is still extremely low. There just isn’t the buildup of excess in the economy that usually precedes a significant recession. This time around, money came in from fiscal measures, demand spiked, and companies responded not by adding excess capabilities but by raising prices. Now we’re on the other side of that curve. It’s tough going from 5% GDP growth to 2% or maybe a bit lower. But to me, it’s going back to a normal environment. And after a few months, the market will recognize there’s still a decent amount of growth happening.

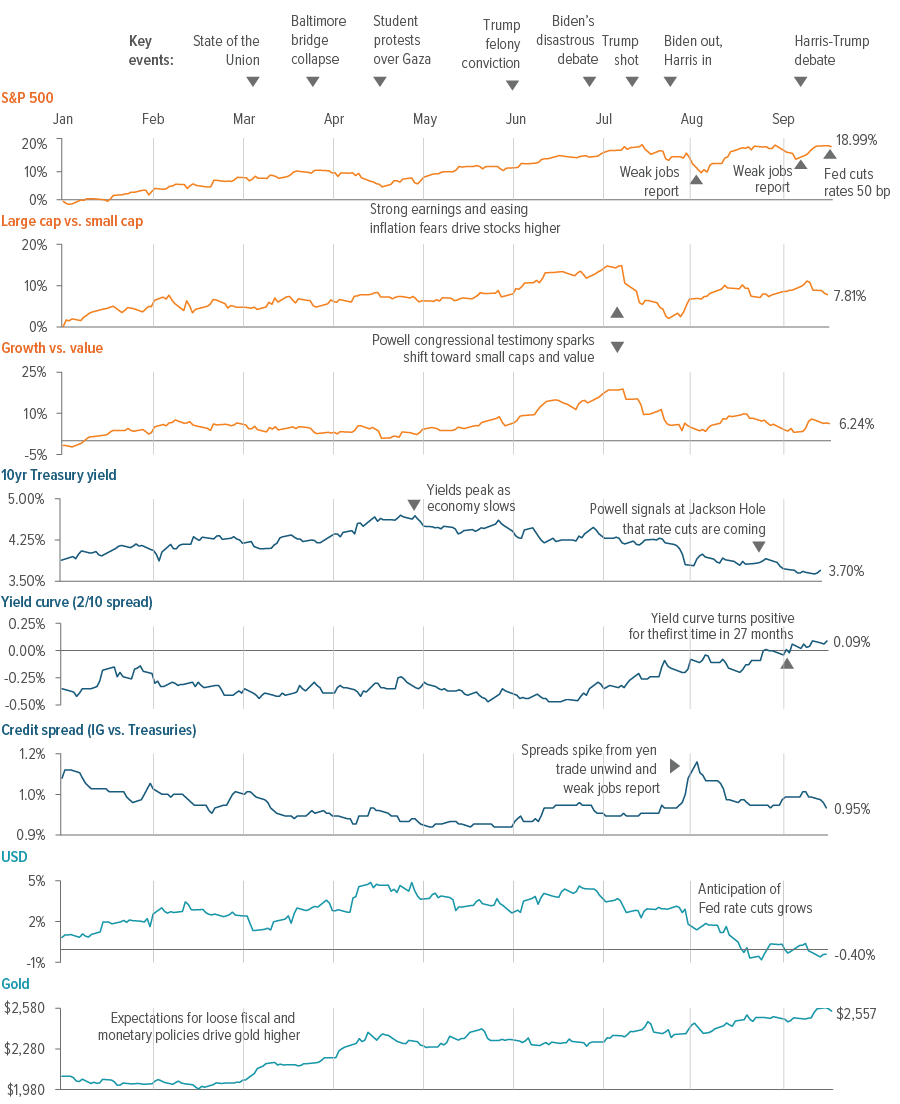

Vincent Costa: We’re also seeing a bit more broadening out of the market as the selloff in early August hit mega caps most acutely, given their incredible concentration in the U.S. equity market. Adding to that, there’s a sense that the more rate-sensitive sectors will benefit from lower yields, so neglected areas of the market such as small caps and value started to catch a bid, creating a more diversified bounce back in equities (Exhibit 1).

James Dorment: I’m kind of “Occam’s razor” on the economy, where the simplest answer is usually the right one. The Treasury curve just disinverted in early September after 27 months—the longest period of inversion on record. And as much as the inverted curve gets attention as a recession indicator, historically, the predictive power really rests with the disinversion. Because the circumstances under which markets anticipate Fed cuts are, in and of themselves, recessionary. That’s a simplistic take on an otherwise complex topic, but we’re taking a more defensive mindset with our value portfolios, which I think is corroborated by the shift toward defensive sector leadership.

Reinhard: I understand the concern regarding subprime auto and other credit related delinquencies rising. But on the whole, the data tell us the U.S. consumer is not tapped out. I do expect consumer spending will start to slow over the next year as households draw down their savings and as labor markets moderate. In terms of the consumer, the Fed’s upcoming rate easing cycle should be seen as justified by sustainably lower inflation.

A lot hinges on corporate earnings. U.S. earnings growth is projected to be 8% for 2024. That looks about right, in our view. The question that will surface after the election is whether the market’s 14% earnings growth estimate for 2025 can be achieved. We think that expectation is far too high and will need to be adjusted downward.

Earnings growth

2024’s 8% S&P earnings growth consensus is reasonable, but 2025’s 14% is far too high.

Stein: So, some different ways here to look at the disinversion story. And a good example of why we don’t dictate a top-down, firmwide macro view to our teams at Voya.

As of 09/18/24. Source: YCharts. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, World Gold Council, Voya IM. S&P 500 Total Return Index. Large/small: Russell 1000 Index vs. Russell 2000 Index. Growth/value: Russell 3000 Growth Index vs. Russell 3000 Value Index. 2/10 spread: 10yr minus 2yr Treasury Constant Maturity (not seasonally adjusted). Credit spread: ICE BofA U.S. Corporate Index minus spot Treasury curve. USD: ICE U.S. Dollar Index. Gold: Spot price per ounce.

Mark Phanitsiri: Let me add two things about the ambiguity in the data around a potential recession. Some of the old patterns of leading economic indicators have changed since Covid. We shut down the economy for a year, and goods and services reopened at different times. Even three years later, some of the historical patterns that used to move in lockstep are moving at different cadences, which creates more uncertainty around the overall trend.

Stein: That’s a great point. Given the stop/start nature of goods versus services, they’ve been more out of sync since we came out of Covid, shifting back and forth.

Phanitsiri: Exactly. And then the second thing is that we’ve never seen this level of fiscal spending in a non-war, non-recessionary period—spending at a 6-7% deficit-to-GDP at a time when employment is strong. That might raise questions about the long-term outlook, but for now it’s contributing to sustaining the economy.

Kristy Finnegan: Here’s another wrinkle to look out for. Consumers tend to pull back on spending going into elections, whether because they’re discouraged by the negativity or worried about the outcome. I wouldn’t be surprised if consumer data soften heading into the crucial holiday season, just as markets are laser-focused on any sign of tipping further into a slowdown. Then, between Thanksgiving and Christmas, we’ll have five fewer shopping days this year versus 2023, which could have a real impact on retailers.

Out of sync

Some indicators are now moving at different cadences, adding uncertainty about the economy.

Stein: Just bad luck of how the calendar falls this year. Shifting to the bond market, credit spreads have almost completely retraced from August 5th, except for a few components of securitized assets. There’s been strong issuance since Labor Day in both investment grade and high yield. Sure, the dollar has weakened a bit, and mortgage rates could come down as the Fed eases and growth slows. But generally speaking, most components of financial conditions are pretty easy.

Market signals: A veil of uncertainty

Stein: Okay, let’s get into the politics. It’s mid-September. How much are financial markets focused on the election?

Dorment: There’s a veil of uncertainty that’s working its way into the complexion of the market, and investors don’t seem to be committing much capital in either direction yet. When I look at the micro themes that have the most beta to a particular outcome—carbon renewables within energy, or Medicare Advantage exposure within health care—the market is telling us that the election is still a coin flip.

Reinhard: Right now, the attention is on central banks, interest rates and economic risks. That could change as we get closer to election day, and you could have some volatility if it looks like a sweep one way or the other.

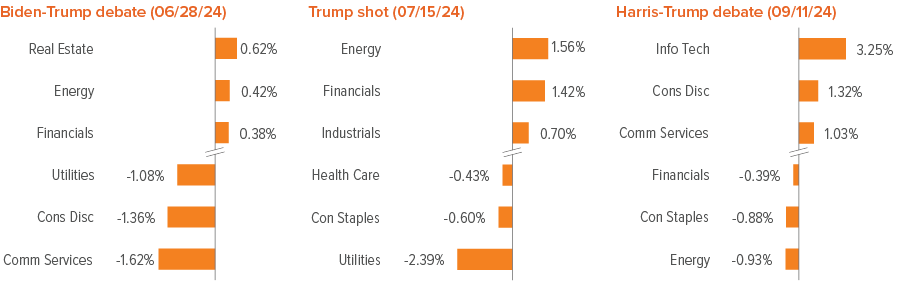

Stein: We saw that in the market’s reaction after the Trump assassination attempt in the second week of July. Betting markets priced in 70-80% probability of a Trump win, and there was a big move in the so-called “Trump trade” of various sectors, such as financials and energy (Exhibit 2). Slowly but surely, that unwound, in conjunction with Biden dropping out and Harris becoming the candidate. And then we saw some of the opposite reaction after the Harris-Trump debate.

A 50/50 race

Outcome-sensitive areas of the market aren’t making big moves yet.

Dorment: I’ll give you an empirical litmus test with the “Misery Index,” where you add the unemployment rate and year-over-year inflation. In 15 of the last 16 presidential elections, the incumbent party won if the Misery Index was lower year over year, and lost if it was higher.1 This is muddied by the perception of Harris as an incumbent, but I think she will ultimately have to own that incumbency. The threshold in October will be 7.35 for the incumbent party to win. As of early September, it was 7.02. If unemployment keeps moving up—and if inflation were to reaccelerate (though that’s less likely)—I’ll stand by that as my betting line as to who carries the day on November 5th.

As of 09/11/24. Source: FactSet, Voya IM. S&P 500 sectors.

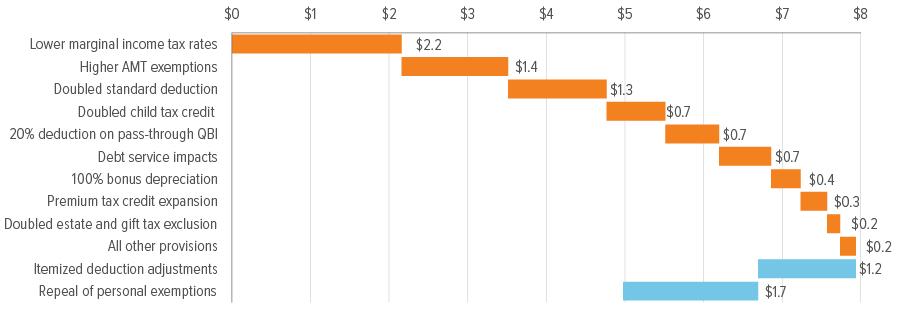

Reinhard: Beyond the presidential race, there’s a huge focus on which party will control Congress because of the 2017 tax cuts that are set to expire at the end of next year. If all the provisions are allowed to expire, we estimate GDP growth will take a 1% hit. I don’t think that will happen, but it means the make-up of Congress will have a big impact on the fiscal impulse for growth in 2025 and 2026.

Dorment: That’s so important because of the starting point with deficits. A sweep by either party would enable a much more meaningful scope of deficit accumulation in either direction, whether driven by spending or tax reduction (Exhibit 3).

Phanitsiri: Well, both parties have become more populist over the last two election cycles. Who would have thought that a lifelong free-trader such as Biden would have kept Trump’s tariffs? Now we have populism A versus populism B, which means fiscal spending will be high either way and deficits will blow up even when there’s no war and no recession. The debate now is over what flavor of tariffs or subsidies to implement against China. In that context, it makes sense that gold is breaking out despite a coin-toss race.

Fiscal support

Though the fiscal mix will look very different depending on the victor, spending will be high either way, supporting demand.

Stein: Right, no one is campaigning on austerity, and there’s no Tea Party pushback the way there was 10 years ago. I suspect a Harris win and a Republican House would be the tightest fiscal outcome, but even that would still be very loose by historical standards. But the mix of fiscal will be quite different depending on the victor.

Phanitsiri: There’s also been talk about taxing unrealized capital gains. Although we don’t know specifics, this is unprecedented and could create new selling pressure on quality compounder stocks, not to mention stifle innovation. I’d be very surprised if that actually moves forward.

Dorment: So you have this world of fiscal looseness. Could we see a return of bond vigilantism?

Stein: James Carville had a great quote in the ‘90s. He said if there was reincarnation, he wouldn’t want to be a .400 baseball hitter or the Pope—he would come back as the bond market because you could intimidate everybody. Every time Treasuries sell off 50 or 100 basis points, I get questions about bond market vigilantes, but then the issue goes away. The U.S. benefits from the rest of the world’s problems and the relative attractiveness of the safe haven status and liquidity of Treasuries. We’ll have to do a lot more damage before that becomes an issue— though it certainly seems we’re doing our best to try!

Bond vigilantes at bay

Despite a rising deficit, the U.S. remains the world’s haven for safety and liquidity.

Banai: America is still the cleanest dirty shirt. There’s just too much money in circulation, so any time the yield curve goes higher, cash pours in and keeps it from rising too far.

As of 05/08/24. Source: Congressional Budget Office, Joint Committee on Taxation, Bipartisan Policy Center, Voya IM.

Red sweep: A deregulation revolution?

Stein: Let’s turn to some specific scenarios. Say that Trump wins, Republicans take the vacant Senate seat in deeply red West Virginia and keep the House. What happens then?

Reinhard: If he follows through on tighter immigration controls and raising tariffs— which he probably can with a sweep—that would likely knock a half a percentage point off GDP growth for the first year. That could cause some indigestion in the markets, simply because we’re in a slowdown. If the economy were on the upswing, it wouldn’t matter as much. But we know what a Trump victory looks like in terms of deregulation, which could benefit some small cap names and some of the energy and financial sectors. That’s what we saw the day after the debate with Biden and after the assassination attempt, when Trump’s probability of winning spiked.

Trump beneficiaries

- Energy

- Finance

- Medicare Advantage

- Crypto

Finnegan: I think the market goes up even if immigration and tariffs impact GDP in the near term, because markets would view a broader extension of the 2017 tax cuts and a lower corporate tax rate as net favorables.

Dorment: Barbara, you mention deregulation. I think this is a powerful idea that isn’t fully baked into the market. The Supreme Court just reversed 40 years of Chevron deference, in which federal agencies were given the flexibility to interpret how to enforce regulations in certain gray areas of the law. After this ruling, that deference shifts to the executive. So for anything that isn’t explicitly stated in the legislation—which happens a lot, because you can’t predict every scenario that might arise in the future—the president will now be able to tell the agencies what they can and can’t do.2

Defanging the regulators

Presidents, not agencies, now have much wider latitude to direct enforcement of regulatory gray areas.

A Republican administration converging with this post-Chevron ethos could set up a “Reagan revolution” level of broad deregulation. We’ve been taking a closer look at companies’ “regulatory beta,” because I don’t think the market grasps the depth and breadth of implications of an executive branch that’s eager to take away the discretion of a lot of regulators. My guess is that Democrats will confer quite a bit of latitude to the agencies, whereas Republicans seem very eager to defang regulation.

Banai: Regulation is often the biggest cost for small businesses. So reduced regulatory costs, combined with lower financing costs, could be pretty powerful given that small businesses make up half the U.S. economy. The concern for me is whether borrowing and deregulation and tariffs reignite inflation. Markets could react pretty strongly on the downside if we get a 3% or 4% inflation report. But I’m not convinced the Republicans would actually implement the kinds of tariffs being discussed.

Dorment: Let me add that a Trump win would be accompanied by regime change at the Federal Trade Commission, which could usher in nothing short of a renaissance in M&A. That would be a windfall for capital market stocks.

Phanitsiri: You’d also have to look at Medicare Advantage names. Trump has been pretty vocal about continuing to privatize the 65+ market. He’s also pressuring energy companies to produce more. A lot of companies have said they’re not going to change their capital discipline, but I imagine there would be some positive sentiment around energy stocks.

Blue sweep: Building from the middle up

Stein: Okay, on the other side, Harris wins and brings along Montana’s Jon Tester and key battleground districts in the House for full control of Congress. How would markets react?

Banai: I think you could get a negative reaction over concerns that a narrower extension of tax cuts and a higher corporate tax rate could mean slower growth. Whereas the Republicans seem less interested in matching borrowing with additional revenues beyond tariffs, Harris is proposing a higher tax on corporations and higher-income taxpayers. There’s an argument that the more you build the middle class, that will improve growth over the longer term.

Harris beneficiaries

- Renewable energy

- Homebuilders

- Staples

- International equity

Costa: Some key themes in equities would be industries that benefit from federal tax credits, such as renewable energy, homebuilders and staples. International equities could also work better on a relative basis if there’s some relief from tariff threats, compounded by a potentially higher U.S. corporate tax rate that causes some migration to non-U.S. exposure.

Reinhard: One thing to think about is whether active Treasury issuance continues in a Democratic administration. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen—who knows how the plumbing works—has been issuing a lot of front-end bills that act like “shadow quantitative easing.” A large part of current deficit spending isn’t from non-defense discretionary spending, which gets most of the headlines during budget battles. It’s from the interest service cost. There seems to be a big willingness, at least on the Democratic front, to stimulate asset valuations from both monetary and fiscal sides.

Stein: We saw a big move in tech after the Harris-Trump debate, though there are a lot of other things going on there as well. But it raises the question—who does Silicon Valley want to win?

Finnegan: I sense the tech world is wary of both parties, but in different ways. A Harris administration could be seen as more antagonistic given greater regulatory pressure, and the Biden Justice Department has been more active against large tech monopolies, with Google and Apple and then the recent Nvidia investigation. But Trump historically has not been seen as favorable to this group either. Take Tesla, where Trump has been generally against clean technologies and electric vehicles. But now they’re clearly shaking hands behind the scenes, so it’s less clear how that will play out. Also, if Harris maintains tariffs at current levels, that could be a positive for Amazon, which would bear the cost of Trump’s proposed higher tariffs on Chinese goods.

Small business

Harris’s support for small business tax incentives underscores bipartisan focus— but different approaches.

Phanitsiri: Trump has been stronger for the dollar, which indirectly helps tech. But the bigger issue gets back to deregulation. The most significant gating factor in the buildout of AI is how to electrify all these data centers. The grid isn’t ready for the load. While renewable projects are helping add supply, it’s not enough—and current regulations are effectively blocking new thermal generation facilities. A new EPA rule finalized in April requires baseload fossil fuel plants to have 90% CO2 capture by the end of 2031. If a natural gas facility doesn’t meet the requirement, it won’t be allowed to operate. We expect this rule to be litigated (ERCOT is already bringing suit), and Harris seems to have eased her stance on restricting traditional energy sources. But to the extent Trump could overturn these new EPA rules, that could be a big deal for building out the grid.

Big picture: Don’t lose sight of what matters

Dorment: I’d like to offer, if I may, an outcome-agnostic trade.

Stein: Okay, let me guess—buy value?

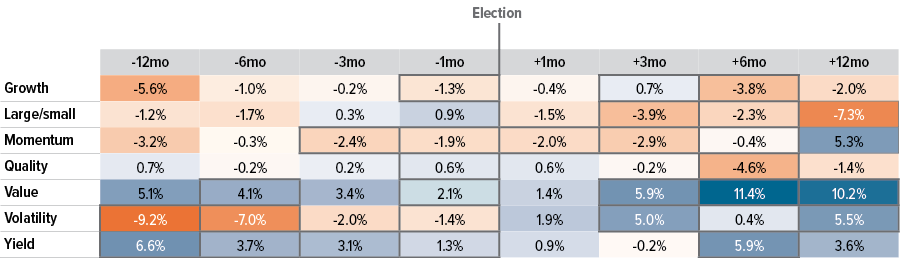

Dorment: I realize it sounds self-serving, but Barclays backs it up with some analysis of the last 10 elections, showing that the value factor outperformed by an average of over 1000 basis points in the 12 months after elections (Exhibit 4). Small caps also generally outperformed their large cap counterparts.

As of 08/20/24. Source: LSEG Data & Analytics, Bloomberg, Barclays Research. “Factor Findings: Rate Cuts and Elections.” Barclays U.S. long/short factors are sector-capped at 20%. Boxed cells highlight returns that were positive (or negative) in more than 66% of episodes. History has been extended to 1984 when possible, covering 10 U.S. elections.

Stein: I love it. Not talking your book at all. Let me ask another question. From an investor perspective, how fast will you have to position for different scenarios? And does that opportunity come before or after the election?

Banai: I think it’s very difficult to put on a directional trade before the election, and the pricing is going to be quick. Volatility might go up on either side of election day. You could see the yield curve change slightly. But a key point is that the trajectory to the economy might get better in certain outcomes—but not worse.

Reinhard: There was some academic research in 2014 showing that prior to the ‘70s, whatever the market did right after the election was often the opposite of how stocks performed over the course of the administration.3 Today, you have to take the market’s initial reaction with a grain of salt, as there is almost no correlation between returns the day after and the next four years. However, a contested election could hang over markets beyond November 5th. We may get a relief rally if we simply have a definitive winner, with the election over and someone being inaugurated. It’s surreal that this where we are, but call it a Santa Claus rally or an Uncle Sam rally.

If there’s one thing I hope investors take away from this, it’s not losing sight of the ball. Whichever candidate wins, as long as the growth environment remains okay and income growth remains okay, I’m staying long equities, where the main driver of returns is still the macro environment, not necessarily the political outcome.

Banai: And on the fixed income side, if you think the Fed cuts 150 basis points over the next 12-18 months with GDP around 2%, that’s quite an attractive environment. Bond investors don’t like 5% growth, and we don’t like 0% growth. When it’s right in the middle, rate volatility goes down, and bond markets tend to respond well.

Stein: Great, thank you all. And be sure to make time in your schedules to vote.